By Peter Everett

The Fateful Day

Rushing water separates the Dominican Republic from Haiti, water that ran red for seven days in October 1937. It is known as the Massacre River. The water holds memories – it remembers the screams, the bullets, the bayonets – but most of all, it remembers the rise and fall of machetes. It tastes the blood, Haitian blood. Rafael Trujillo, the dictator ruling the Dominican Republic, ordered his soldiers to use machetes (a traditional farming tool) to make the killings appear to be justified, simply Dominican farmers on the border defending themselves from a Haitian incursion. However, the brutality of the massacre belied such a story. At least 12,000 Haitians were killed, and in horrific fashion: babies’ heads were dashed against rocks and impaled on bayonets as their parents were slowly chopped to pieces with machetes.

At the time, the international community rightly compared it to the Rape of Nanking and the Holocaust (Roorda). Neighbors killed neighbors. Many of the Haitians killed had been born in the Dominican Republic; they were citizens. However, because of their ethnicity, their color and culture, many Dominicans believed them to be inferior, to be deserving of death. But how did such an extreme anti-Haitian sentiment develop? Before the two nations were even independent countries, they were at war. Their history is one of intense and constant conflict, and Trujillo would take advantage of that narrative to solidify his control over the very soul of the Dominican Republic. He reinforced Dominican prejudices, confirmed a false conception of Dominican racial identity, and, in so doing, eliminated the bicultural border towns that threatened his authority and cult of personality. In Trujillo’s mind, he was simply taming the frontier.

Colonial Beginnings

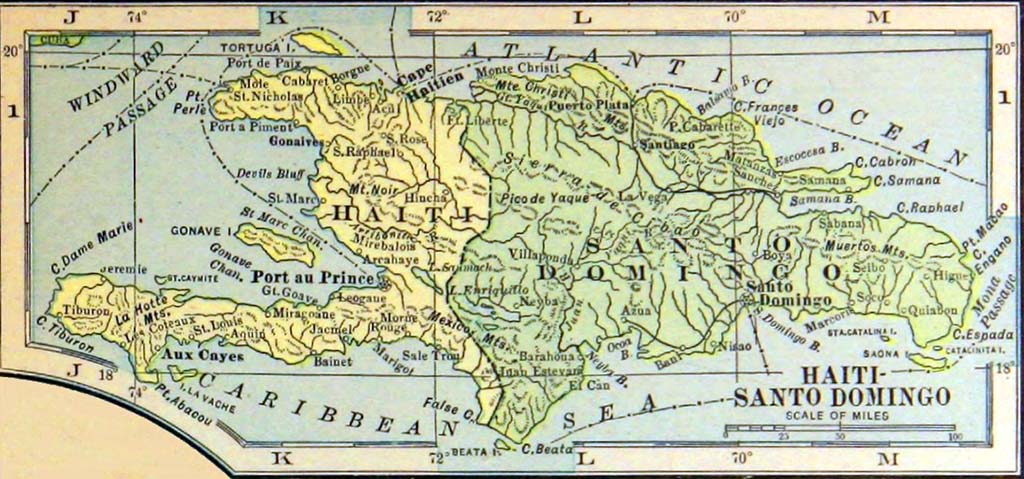

Before the Haitian Revolution, Haiti was a colony of France, while the Dominican Republic, then known as Santo Domingo, was controlled by Spain. As a result, when Spain and France fought for territory, money, and imperial influence, the peoples of Haiti and Santo Domingo were pitted against one another.

Unfortunately, the divisions persisted even after each colony achieved independence, divisions which sprung not only from colonial warfare but also from the cultural values each nation inherited from their European rulers. While the Haitian revolution reflected the values of the French Revolution, values of equality and brotherhood, the Dominican path to independence and the formation of their cultural identity was dictated by economics, and placed them in direct conflict with their Haitian neighbors. As the sugar industry died and piracy flourished, Spain was unable to maintain a plantation economy. The resulting “decay of the plantation and the virtual destitution of whites effectively brought the status of slaves and former slaves to a level identical with that of masters and former masters, breaking down social barriers between the races, facilitating interracial marriage relations, and largely giving rise to an ethnically hybrid population” (Torres-Saillant). In terms of national identity, the outcome was a societal association of blackness with economic poverty and social inferiority, and with that association followed a Dominican denial of their own biological blackness. Instead, they came to call themselves “Indio” a reflection of their perceived mixed and European descended racial identity.

The Dominican War for Independence

In 1822, Dominican revolutionaries, having driven out the Spanish, agreed to ally with the newly formed Haitian government and form one collective nation. However, the Dominicans were deceived. Haiti was paying France a ransom to maintain independence, and Haiti occupied the Dominican Republic with the purpose of inflicting heavy taxes on the Dominican people to pay the debt. The occupation was oppressive, and reinforced the Dominican perception of themselves as an entirely distinct in culture from the Haitians, with a unique language and racial lineage. Eventually, Dominicans went to war to drive the Haitians out, and even after their initial successes continued to defend their border against various Haitian incursions until 1856. As a result, in the Dominican imagination, the Haitians were aggressors, perpetually waiting for another opportunity to invade and destroy Dominican culture.

The Rise of Rafael Trujillo

Though widespread distrust of Haitians always existed throughout the Dominican Republic, distrust resulting from the two nations tumultuous history, Rafael Trujillo managed to transform that distrust into bloodlust. Taking notes from Adolf Hitler, whose “racial theories he clearly embraced,” Trujillo enacted a “racist and nationalistic plan” to consolidate and centralize his control over the country by shifting the blame for various economic crises from his shoulders to the Haitians living in the border towns (Wucker). He called his policy, which involved deportations and various other abuses, “Dominicanization,” a reflection of his emphasis on national identity and solidarity, an identity that Haitians threatened to subvert. To further this narrative, Trujillo employed intellectuals to convince the Dominican people every stereotype they had ever heard about Haitians was true (Veldwachter). They reminded the people of the past wars, the Haitian aggression, and asserted Dominican racial superiority. Haitians were black, the color of African slaves, while Dominicans were Indio, the ethnoracial descendants from the noble Spain. Trujillo’s denial of the Dominican Republic’s multi-racial heritage allowed him to justify the massacre in nationalistic terms, while simultaneously silencing the multicultural border region, which up to that point had defied his authority and, just by existing, refuted his narratives of Haitian inferiority and incompatibility with Dominican culture. He called the massacre a “remedy,” language eerily similar to Nazi uses of the word ‘solution’. As a result, innocent Haitians, some of whom had lived in the Dominican Republic their entire lives, were killed indiscriminately.

The Legacy of the Massacre

To this day, anti-Haitian feeling persists in the Dominican Republic, as Haitian residents are denied citizenship and Haitian workers are denied fair wages, and, in some cases, humane working conditions. The massacre even lives on in the memory of immigrants and the descendants of immigrants, reflected in poetry. However, it is enlightening to view Trujillo’s rhetoric and genocidal policies as not only a war against Haitians but as a story.

The policy created a tale of “Dominicans versus Dominicans, of Dominican elites versus Dominican peasants, of the national state against Dominicans in the frontier, of centralizing forces in opposition to local interests, and following the the massacre, of a newly hegemonic anti-Haitian discourses of the nation vying with the more culturally pluralist discourses and memories from the past” (Turits).

It is a two-pronged tragedy. Not only did countless Haitians lose their lives, and continue to lose their livelihoods and dignity, but the Dominican people have been completely deceived, denied understanding of their history by an oppressive, authoritarian regime looking to consolidate political power with racial politics. And Trujillo made the Dominican people complicit in the act itself, a guilt and a history they now must wrestle with and resolve. The last outposts of cultural pluralism, the last bastions of racial freedom, the border towns, were washed away in a river of blood.

Works Consulted:

- ROORDA, ERIC PAUL. “Genocide Next Door: The Good Neighbor Policy, the Trujillo Regime, and the Haitian Massacre of 1937.” Diplomatic History 20, no. 3 (1996): 301-19. Accessed May 12, 2021.

- Torres-Saillant, Silvio. “Creoleness or Blackness: A Dominican Dilemma.” Plantation Society in the Americas, no. 1 (1998): 29–40.

- Turits, Richard Lee. Foundations of Despotism: Peasants, the Trujillo Regime and Modernity in Dominican History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003.

- Veldwachter, Nadège. “How to Kill with Words: The Convergence of Dominican and German Rhetoric in the 1937 Haitian Massacre.” Journal of Haitian Studies 26, no. 1 (2020): 74–103.

- Wucker, Michele. Why the Cocks Fight: Dominicans, Haitians, and the Struggle for Hispaniola. New York: Hill and Wang, 2000.