By Kendra Soler

freedom in destruction.

Favela community in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty

It’s 2015, approximately a year until the Rio Olympic Games commence. There’s nothing but excitement in the air. Only a block away from the new stadium, in the center of one of the world’s most-watched events. Fresh new faces line the streets, appearing hopeful for what Brazil may provide. As you watch these new bodies walk up and down the area you’ve always known, there is a knock at the door. Curious as to what could be at your front step, you spring up to answer, only to find your parents cautiously peeking out. You back away to hear their faint conversation with whoever is behind the door. And eventually, the sound of your mother crying fills your ears. She’s saying, ‘I didn’t put my house up for sale, so my house has no price. I’m not interested in moving. Why do they think that everything can be bought and sold?'” You are stunned. Struck by the words you hear come from your mother’s mouth. Will this no longer be our home? Months pass, and you have been moving from place to place, unable to call anywhere home. You go back to your old neighborhood from time to time, only to find more destruction with each visit. The very place you called home has been demolished and turned to rubble. In this rubble, you make out pieces of your old room and begin to well up with emotion. You look around to see still new faces, unbothered by the destruction of a place so important to you. And as you begin to look up from the rubble that was your home, you see the construction of something new. You realize what it is and wonder: “In what world would it be okay to destroy homes for the entertainment of others?”

material violence, emancipation, renewal.

The Unearthing of Valongo Wharf in preparation for 2016 Olympic Games.

The unearthing of Valongo Wharf in preparation for 2016 Olympic Games.

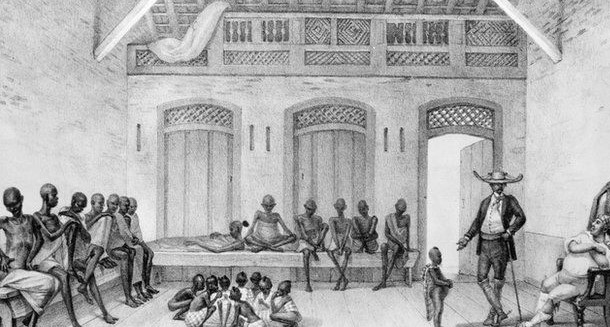

Valongo Wharf was built on the backs of those stripped of their home and their culture. The years of torture and violence the architects and constructors of this site endured are preserved in every stone. Much weight is carried in preserving this historic site, a effort that highlights the tension between remembrance and resilience. The Afro-Brazilian community recognizes the material aspect of Valongo Wharf as a reference to its slave past. Understandably so, the Black community disregarded this portion of their history and allowed it to be covered up. It would be eventually uncovered under specific circumstances, unintentionally exposing this dark history and pushing for its preservation. Simply put, one of the cruelest aspects of the history of slavery in Brazil was accidentally dug up, and when asked what it was or who wanted to preserve it, no one answered the call to action until 2017.

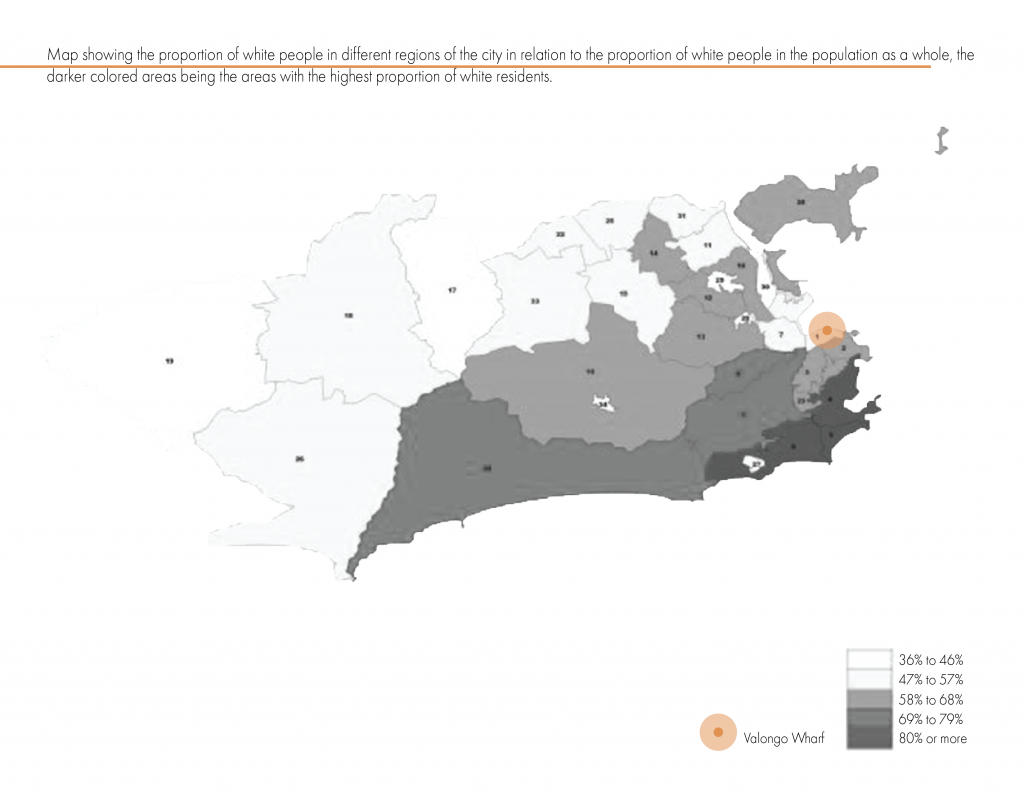

Appropriation, in this context, refers to the process of obtaining something that belongs to another person, people, or culture. Valongo Wharf was not excavated and studied by the Afro-Brazilian population, instead by urban design experts and construction workers preparing for a tourist-driven event. And in understanding this, we may begin to see how those who have the authority to do this studying and digging also can transform the urban landscape and silence history to suit their needs. In is also interesting to consider that Afro-Brazilians have been pushed into primarily labor-driven positions and left out of professional fields such as science and archaeology. However, despite the historical stigma that Black people were inferior, it is also important to recognize that the same people they treated this way were able to build an entire port system and its surrounding communities.

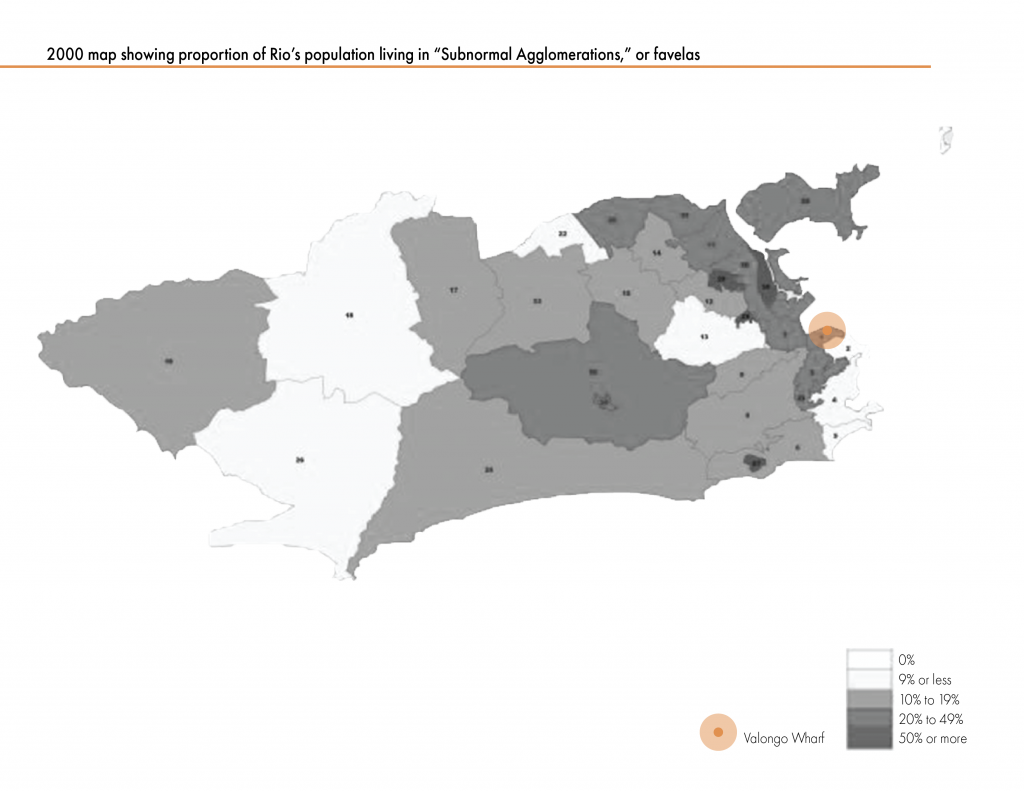

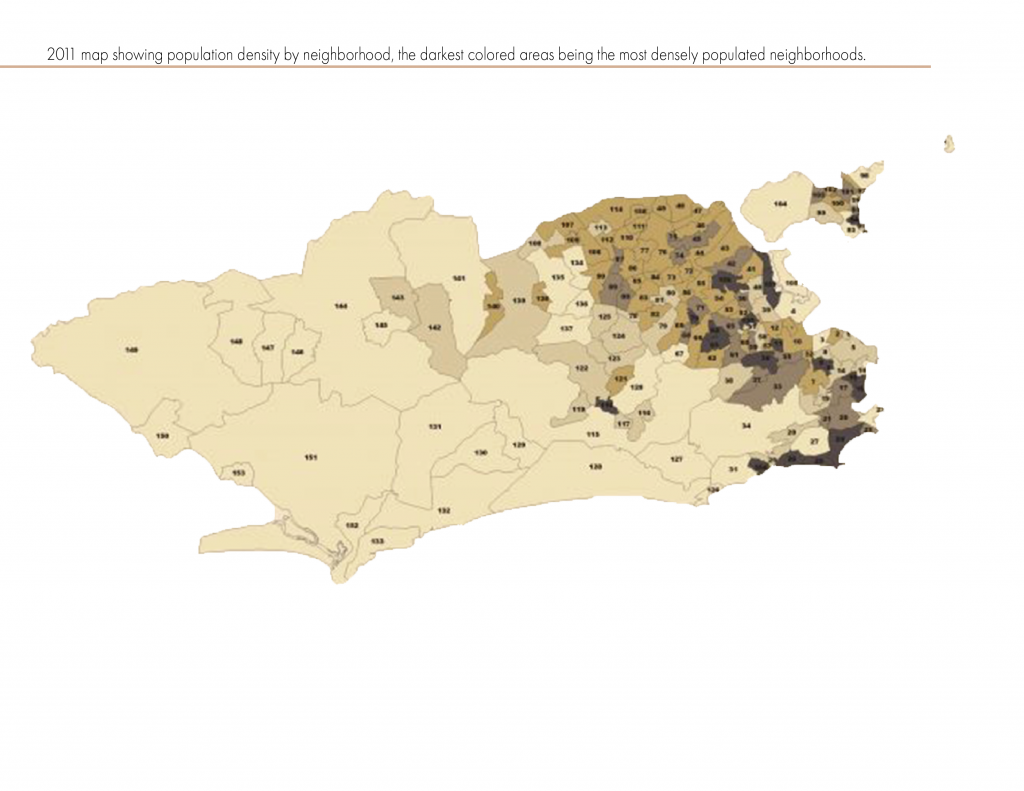

Urban renewal or revival is considered the process by which designers, governmental agencies, and organizations band together to revitalize the built environment in an urban setting. In this process, it is necessary to recognize that many voices and perspectives are left out or ignored. This typically results in the displacement of existing communities, especially in preparation for tourist-attracting events such as the Olympic Games. The economic gain from tourism and urban development casts a shadow on Black settlements, and furthers disparities between them and the city.

“The regeneration of Brazilian cities reinforces the legacy of developmentalist policies in the interest of private capitals with little influence over the making of new places”.

“The Delivery of Rio De Janeiro’s Port Regeneration Project.” Accessed April 11, 2021. https://www.rc21.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/F1-Silvestre-Extended-Abstract.pdf.

Emancipatory Archaeology challenges both urban renewal and developmentalist policies. Emancipatory Archaeology refers to the act of freeing a people and culture from its historical binds by exposing them to the “what was” in hopes that it will benefit the “what is”. The unearthing of Valongo Wharf was a turning point, as it became an outward recognition of the past, and a respect for its subjects through the historical preservation of the site. However, there still remains bias in these processes. In this case, the UNESCO effort to preserve this site is a step in the right direction as far as exposure, and not allowing urban renewal to dictate the fate of Rio de Janeiro’s Black population.

history & context.

At the center of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, Brazil served as the largest slave-importing country in the world. This mass importation made Rio de Janeiro then a Black city, an influence that still can be felt today. Valongo Wharf resides in the middle of this area as an operating point of arrival for slaves. The construction of this wharf was completed in 1811 by slaves and served as a slave mercantile complex till 1831, including space for quarantine, warehouse and market production, and cemetery services, creating a main avenue in this area of Rio de Janeiro. Those weak and thin from their travels were kept in the wharf to recover and gain weight to be sold at slave markets. Eventually, Valongo Wharf’s identity shifted after the arrival of European royalty to the ports of Rio de Janeiro. The wharf underwent renovations in 1843 in preparation for Princess Teresa Cristina’s arrival to transform a known slave port community into a place accepted by those in the highest order. Valongo was renamed Empress Wharf. The name change lives on today, as many consider the original site of Valongo Wharf the relatively formal Empress Wharf in pursuance of alleviating the stigma of slavery for good.

Assumably, at some point after its operation concluded, the site of Valongo Wharf was covered up. The wharf was eventually unearthed in 2011 for the 2016 Olympic Games, after serving as a simple parking lot for the many years before. Even after the unearthing, the community remained distant and disassociated with the history of Valongo Wharf. Brazil, notorious for its race-transcended ideals, buried this history intentionally. The White people of Brazil disassociated with the site because they were ashamed of their history of subjugating Black people, while people of African descent disassociated with it because of their shame in the oppressive history that created it. And in this shame came silence and distance from the Black Brazilian community. However, this silence did change once prominent Black community and movement leaders stepped up and expressed the value in witnessing one’s history; no matter how triumphant or oppressive. Close-knit Black settlements called favelas hit a pivotal point in their existence, especially that of Pedra do sal or “little africa” residing only a five minute walk away from the site of Valongo Wharf. This large shift in mindset provided the Afro-Brazilian community the opportunity to fully recognize their race, which allowed them to create deeper ties with their original African heritage.

To conclude this history, it is essential to mention that Valongo Wharf has been officially declared a UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Heritage Site. Understanding the basis of world heritage sites allows us to grasp the lessons we must learn from history.

“Valongo Wharf is considered one of the most notable places of memory of the African diaspora outside of Africa itself and compared to Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Gorée Island, and Robben Island, Valongo was understood as a location that encapsulates memories of pain and struggle for survival in the history of the ancestors of Afro Descendants. These sites, testaments to large tragedies in the history of human societies, were transformed into world heritage sites so that they can serve as a reminder of the horrors committed by humanity, seeking to prevent them from ever being repeated”.

Lima, Tania Andrade, Marcos André Torres de Souza, and Glaucia Malerba Sene. “Weaving the Second Skin: Protection Against Evil Among the Valongo Slaves in Nineteenth-Century Rio De Janeiro.” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 3, no. 2 (2014): 103–36. https://doi.org/10.1179/2161944114z.00000000015.

As powerful as this message and lesson may be, preserving the site has not halted the urge to renew and revive the Rio de Janeiro urban area. There is a tension between preserving history, reminding people of a past they don’t want to know, and pushing for the continued ‘improvement’ of the urban environment without existing communities in mind. Recognizing this tension is crucial in addressing both the more significant issue of tourism-gentrification and the more refined issue of preservation’s role in interpreting Afro-Brazilian heritage.