Matthew Reich

“My mother Thetis tells me that there are two ways in which I may meet my end. If I stay here and fight, I shall not return alive but my name will live forever: whereas if I go home my name will die, but it will be long ere death shall take me. To the rest of you, then, I say, ‘Go home,”

– Achilles, in The Iliad by Homer, Translated by Samuel Butler

Statue of Achilles in Hyde Park, London, from researchgate.net

Who is Antonio Maceo?

Antonio Maceo was a general in the Cuban revolutionary army and fought against the unjust oppression of his home, Cuba, by the Spanish. He became a powerful leader, fighting for autonomy, not for control or conquest, maintaining a moral and ethical stance. His life seemed to follow a heroic template laid out thousands of years before which led to his image and reputation becoming such powerful tools for modern movements. His Heroic image aligns with classical conceptions of heroism and embodies my definition of a ‘moral hero.’ However, to analyze these connections between Maceo and the classical world, we first need to define a classical hero and the characteristics of a ‘moral hero.’

What is a Hero?

For millennia, the Heroes of myth have entranced humans, providing the West with stories that convey concepts of morality, strength, loyalty, and pain. Myth has informed the image and reputation of powerful figures since the Greeks invented them. The Iliad contains two of the most powerful classical heroes, Achilles, and his counterpart, Hector. In the opening quote, Achilles contemplates the decision that all Heroes are forced to make: the decision to take the more challenging path, fight for something bigger than oneself, be placed at the forefront of history, or be content with a life without more significant meaning. His enemy, Hector, represents another form of Hero, faced not with the question of reputation but with survival. Hector is challenged with defending his home, the city of Troy, against the attacking Greeks after his brother’s misguided antics with the beautiful Helen. He is tasked with protecting his family against the vicious invaders. As a humble father and unenthusiastic fighter, he is matched against the famous Achilles, the most powerful Greek warrior in history–and is struck down. Hector’s loyalty and dedication to his home contrast the violent and unstable Achilles. Hector fought to defend his home, never aggressing, chasing the Greeks onto their ships, but not pursuing them further. Achilles, in contrast, killed any man who came before him after the death of Patroclus, clogging the river with the corpses of his enemies. The differences between the two heroes are vast; therefore, to continue to refer to all heroic individuals as ‘heroes’ is woefully inadequate. I define Hector as the premier ‘Moral Hero.’ He fights for a just cause against any odds, defending his family and home.

The Creation of Heroic Image

Classical heroes all tend to follow a similar path. Firstly, they are assuredly not merely mortal to some degree. This can be explained through some inhuman characteristic, or more commonly through divine lineage. Secondly, they have a powerful physical presence, large size, immeasurable strength, handsome features. This aids in their description as not wholly human. Third, classical heroes are brave, steadfast, loyal, pious, and moral; however, generally, classical heroes lose connection with this in battle and enter a berserk rage where they commit autonomous violence. This violent episode, in the classical world—the myth’s intended audience—was meant to convey the brutality of war and the necessity of maintaining one’s humanity in war. Moral heroes, as a rule, do not commit this violence, instead, they retain their higher moral and ethical stance. Fourth, heroes travel, sometimes for extended periods, where they are tested and taught lessons integral to their cultures. Lastly, classical heroes had an apotheosis, meaning that they were deified, chosen by the gods to join them in heaven, immortal. Maceo, through the facts of his life, the memory crafted by his contemporaries and the history written by those more recently, fulfills the characteristics of a hero and, more specifically, my requirements for a moral hero.

Statue of Antonio Maceo on Horseback, Located in Santiago de Cuba, from equestrianstatue.org

Maceo as a Moral Hero

As documented in “A Tribute to Antonio Maceo,” Maceo was remembered by his contemporary J. Syme-Hastings, who described him as “a man of magnificent stature, with just enough of the lion about him to make him a leader.”[1] Immediately upon Maceo’s death, imagery surrounding classical heroes is used to shape his memory in our collective consciousness. His physical presence is inhuman, described as having a “magnificent stature,” leaving the audience wondering what magnificent means regarding physical height or presence. His description as involving a “lion” is also not a coincidence. The first labor of Hercules, he fights the Nemean lion, establishing lions and other great predators from the outskirts of the Mediterranean world as heroic conquests, but importantly, Hercules then wears the Nemean lion skin as a prize.[2] By describing Maceo as having an amount of the lion in him, Syme-Hastings implicitly compares Maceo with Hercules, the pinnacle of classical heroes. Syme-Hasting wrote a poem after hearing of Maceo’s death. In it, he wrote, “They have filled him full of bullets…and beheaded him a dozen times or more…but he manages to live…for the lives of this fellow Maceo has a score,” depicting the recently killed Maceo as an immortal figure.[3] Syme-Hasting describes Maceo as physically invulnerable, connecting Maceo with the feats of Achilles, whose skin was impenetrable in battle. However, while on the surface, the poem seems to argue that Maceo has literally not died, on another level, the narrator is arguing that Maceo has reached his apotheosis: an ascent to heaven or deification. As a narrative device of the classical period, the apotheosis described a hero joining the pantheon of gods on Olympus. Although Maceo lived and died far after Pagan times, he is immortalized in a shared collective consciousness through the poem. Maceo’s battle for Cuban independence was also a broader battle against racial oppression. As noted by Johnetta Cole, “Maceo’s blackness was revered as his fight went against widespread ideas of racial superiority and was a powerful image for black populations autonomy.” [4] His military prowess and ethical stance were known internationally as his name became, before and more so after his death, synonymous with racial and freedom struggles.

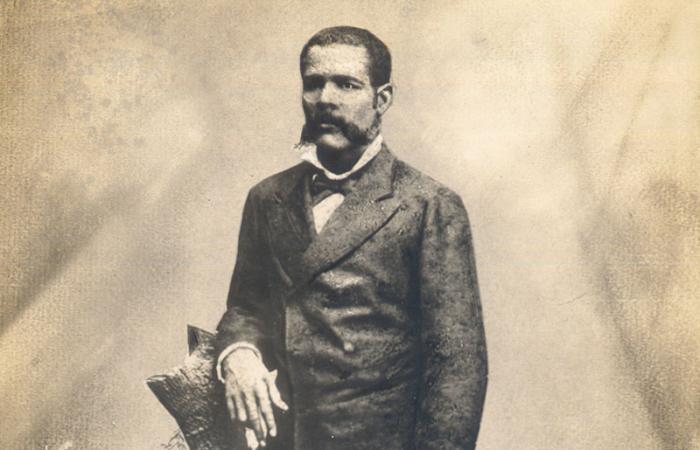

Antonio Maceo, Portrait from thecubanhistory.com

More than the Classics

The injustices present in Cuba that Maceo fought against were inherently racialized along color lines, a phenomenon not found in the Ancient world in the same way. However, Maceo’s morality and strength solidify his identification as a Moral hero even though the specific challenges he faced were vastly different than those faced by classical heroes. For example, the association of Maceo to a classical hero woefully ignores the importance of race during Maceo’s time. When drawing connections between such different environments as 19th century Latin America and the ancient world, it is important to note different understandings of race and nationality. Classical heroes represented, almost exclusively, the dominant culture of their time. They were strong Greeks and virtuous Romans, descended from the very gods that their contemporaries worshipped. Concepts of race and foreignness were quite simply different than the level of division and conflict seen in relatively recent Latin American history. The racial struggles that Maceo faced did not exist in the ancient world.

In the decades before Maceo’s birth, sugar plantations in Cuba increased production and required more slaves to surpass Saint-Domingue’s role as “the premier colony of the new world.”[5] Hundreds of thousands of African slaves were shipped to Cuba, placed into a world where they were forced to work under threat of “the machete and the whip.”[6] Maceo was born into a world where humans, all around him, just like him: with dark skin, were dehumanized and brutalized for profit, and Maceo fought against that system tooth and nail. He never wavered in his goals for equality and independence for his home: Cuba. He faced challenges considerably different than those faced by heroes in antiquity. However, his tackling of those challenges and the image he portrayed make him an exemplar moral hero even if his circumstances were different, rather expectedly, than those of the ancient world.

Immortality

Even as Maceo’s memory is steeped in the lexicon of the classical world, his influence and image is widely used to further racial and nationalistic movements in the Caribbean and Latin America. Across the Americas, Maceo’s name adorned the titles of groups as a “statement of inclusivity” to signal that clubs “welcomed all Cubans and offered them an equal opportunity.”[7] Maceo’s name continued to represent the values that he fought so hard for. Even after his death, or perhaps especially after his death, his name stood alongside calls for independence and equality. Through the survival of Maceo’s name, Maceo’s concepts of a better world continued. While the man may have died and his body buried long ago, his heroic goals live on. Maceo lives on through his reputation as a moral hero.

Notes

[1] Syme-Hastings, Journal of the Knights of Labor, (November 1896). In Foner, Philip S. “A Tribute to Antonio Maceo.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 55, no. 1 (January 1970): 66.

[2] Harris, Stephen L, and Platzner, Gloria. “Heroes at War: The Troy Saga.” In Classical Mythology, Sixth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, 2012. 290.

[3] Syme-Hastings, Journal of the Knights of Labor, (December 1896). In Foner, Philip S. “A Tribute to Antonio Maceo.” The Journal of Negro History, vol 55, no. 1 (January 1970): 66, 67.

[4] Cole, Johnetta. “Afro-American Solidarity with Cuba.” The Black Scholar, vol. 8, no. 8/9/10 (Summer 1977): 74, 75.

[5] Ferrer, Ada. “Speaking of Haiti: Slavery, Revolution, and Freedom in Cuban Slave Testimony.” 225.

[6] Ferrer, “Speaking of Haiti,” 227.

[7] Muller, Dalia. “Cuban Revolutionary Politics in Diaspora.” In Cuban Emigres and Independences in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf World. University of North Carolina Press, 2017. 99.

Works Consulted

Bowra, C. “Aeneas and the Stoic Ideal.” Greece & Rome, vol. 3, no. 7 (October 1933): 8-21.

Carrasco, Jorge. “Raising the Cuban Flag: Comics, Collective Memory, and the Spanish-Cuban-American War (1898).” In Comics and Memory in Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017. 33-58.

Cole, Johnetta. “Afro-American Solidarity with Cuba.” The Black Scholar, vol. 8, no. 8/9/10 (Summer 1977): 73-80.

Fagen, Patricia. “Antonio Maceo: Heroes, History, and Historiography.” Latin American Research Review, vol. 11, no. 3 (1976): 69-93.

Farron, S. “The Character of Hector in the “Illiad.”” Acta Classica, vol. 21 (1978): 39-57.

Ferrer, Ada. “Speaking of Haiti: Slavery, Revolution, and Freedom in Cuban Slave Testimony.” 223-247.

Foner, Philip S. “A Tribute to Antonio Maceo.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 55, no. 1 (January 1970): 65-71.

Harris, Stephen L, and Platzner, Gloria. Classical Mythology, Sixth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, 2012.

Hay, Robert P. “George Washington: American Moses.” American Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 4 (Winter 1969): 780-791.

Muller, Dalia. “Cuban Revolutionary Politics in Diaspora.” In Cuban Emigres and Independences in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf World. University of North Carolina Press, 2017. 83-131.

Syme-Hastings, Journal of the Knights of Labor, (November 1896). In Foner, Philip S. “A Tribute to Antonio Maceo.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 55, no. 1 (January 1970): 65-71.