By Fielding Lewis

From Colonization To Maradona

At the 2018 World Economic Forum Mauricio Marci, who was president of Argentina at the time, declared that Buenos Aires was “the Paris of South America.” It was not the first time that a state official used language to deny African influence in Argentina. Oddly enough, in a 1993 speech at historically black Howard University, former president Carlos Menem use similar erasures to encourage economic investment in the country. Menem said: “We don’t have blacks… that’s a Brazillian problem.” (Goñi, 1) Whether they were conscious of it or not, Marci and Menem’s remarks added to a false narrative about their country’s history. This false national narrative can be contradicted at every stage of the nation’s development from independence to when football legend and national hero Diego Maradona, a man of mixed racial heritage, took his last breath.

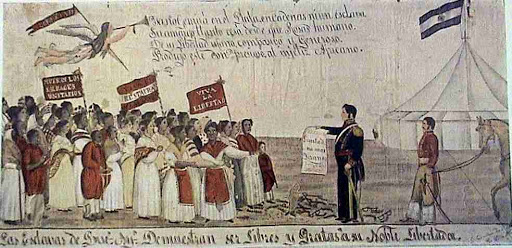

In 1778 the Spanish empire took a census of an area referred to as the Viceroyalty of the River Plate, which encompasses modern-day Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Of the 420,000 people who were accounted for, 37% identified as “African,” and out of 25,000 who resided in Buenos Aires, 29.7% identified as African, otherwise referred to as Afro-Porteño. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, these percentages stayed roughly the same, even as the city population rose to over 60,000. A stark contrast from the makeup of the country today which identifies as 97% white. (Andrews, 69) This may lead you to ask, “What happened to the Afro-Porteños?” For many in Argentina, they believe it’s a mystery. There’s an idea that people of African descent died out, or moved away. Some may even recognize the ethnic cleansing that took place throughout the second half of the 19th century as a cause for their disappearance. Still, few acknowledge that the majority of the Afro-Porteños never left, and that they themselves may be the ones carrying on their legacy. One way to disprove the modern narrative on race in Argentina is to examine the social artifacts of when people of African descent supposedly started to disappear. One artifact, in particular, shows a juicy contradiction, the Afro-Porteño press.

The man, the legend, Diego Maradona (Goñi, 1)

“Gobernar es Poblar”

Halfway through the 19th century, a movement started amongst the ruling and intellectual classes to whiten their current population and the historical image of the nation. One of the biggest proponents of this idea was Juan Bautista Alberdi, a political theorist. He coined the nationalistic slogan “Gobernar es Poblar” in his 1853 book Bases and starting points for the political organization of the Argentine republic. Alberdi and the newly formed government’s goals were reasonably clear. They wanted to increase the country’s population drastically, but only with people of a specific skin tone. Alberdi wrote, “To populate is not to civilize, but to brutalize when populating with Chinese and Indians from Asia and blacks from Africa.” To get white people to move to the tango nation, the government incentivized European immigration. From 1853-1887 the population of Buenos Aires exploded from around 65,000 people to over 4,333,000 due to this incentivized immigration.

In contrast to this growth, the population of people who identified as Afro-Porteños dropped from around 15,000 to 8,000 people. The reason for this growth is relatively apparent. From 1853-1930 over 6.6 million Europeans immigrated to the country, with the majority of them passing through the port city of Buenos Aires. This makes Marci and Menem’s statement make sense, even if it is draped in racist ideologies. In some ways, Buenos Aires is the Paris of South America, but only in the same sense Disneyland’s Epcot is home to every country on the planet. For decades, people in power attempted to fill the city not just with people who resembled Parisians, but also with cultural ideas and architecture that resembled the French city. Marci, Menem, and others may stick to their claims. But ignoring the influence that people of African descent had on the city is not only wrong; it erases their tangible cultural, political, and social contributions to the country. Sure, a lot of people might want to go to Epcot, but I can promise you the ceviche is going to taste better in Quito than in Orlando.

Hot off the Press

As the Afro-Porteño population dwindled and history was being rewritten, one aspect of Black culture was thriving, its press. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, over 306 different newspaper publications were run by and catered to people of African descent. At that time, the press played an important role in social change, politics, and culture, and was the primary mechanism used to spread information(Geler, 2). Although many of the original papers have been destroyed, their mere existence disproves the narrative that Argentine leaders from Juan Alberdi to Mario Marci have attempted to create. When you deconstruct that narrative, it’s clear that Afro-Porteños not only existed but played an essential part in society. Politicians and members of Argentina’s ruling class not only had to recognize the existence of their non-European counterparts, but they also needed them to push their narrative. The ruling government and bourgeois class, made up almost entirely of whites, recognized the influence Afro-Porteño newspapers wielded politically. The white bourgeoisie class needed editors of non-homogeneous papers to advance the state’s agenda and keep people of African descent from intervening in a public way. This kept the myth alive that Afro-Porteños had simply disappeared, while in return, the marginalized community was awarded at least some level of agency. (Geler, 20)

Black Agency

The existence of 306 Afro-Porteño newspaper publications during five decades is enough evidence to prove that people of African descent didn’t simply disappear from the country’s capital. These publications were read almost exclusively by people of African descent but were still capable of influencing the larger mainstream white culture. At the time, the press was considered by both marginalized communities and the white ruling class as being a tool for progress and civility. The European concept of civilization did pressure Afro-Porteño publications to assimilate to what white’s viewed as “modern.” Still, the Black press could act as a mediator between the marginalized community and the dominant groups. One example of this relationship is how the Afro-Porteño press routinely convinced the police to ignore segregation laws during carnival. In exchange, political protest and demonstrations by people of a darker skin tone were held outside the city center and out of the view of the whites. (Geler, 24) Like with most liberal movements throughout history, the value of this compromise can be debated, but the influence the papers yielded is irrefutable.

The Big Picture

Today few Argentines will tell you or even know about their African heritage. After centuries of racist ideologies and governmental policies, most Afro-Porteños have assimilated into a homogenous culture that emphasizes European heritage and ideals over the country’s history of racial mixing. Pierre Norah said that history separates from memory when a society starts analyzing the history of its history. It seems that in the case of many Afro-Porteños, there may be a reluctance to examine their past to avoid cognitive dissonance between their ancestry and their country’s racist myth. When considering the late Diego Maradona, a man who self-identified as white, but who was often referred to as “negro,” you start to understand how that myth was upheld not just through policy, but also through control of national narratives that erase the African influence.

Works Consulted

-AFROPUNK. “Argentina’s Black Population Has Been Systematically Erased & Removed

in Whitewashing Effort.” 19 July 2018.

-Andrews, George Reid. The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires: 1800-1900. University of Wisconsin Press, 1980.-Geler, Lea. “Afro-Porteño Newspapers and Journalists in the Late 19th Century.” Translating the Americas, vol. 4, no. 20190612,2017,doi:10.3998/l acs.12338892.0004.001.

-Goñi, Uki. “The Hidden History of Black Argentina: by Uki Goñi.” The New York Review of

Books, 8 Feb. 2021.

-Geler, Lea. “Afro-Porteño Newspapers and Journalists in the Late 19th Century.” Translating the Americas, vol. 4, no. 20190612, 2017, doi:10.3998/lacs.12338892.0004.001.

-Karush, Matthew B. “BLACKNESS IN ARGENTINA: JAZZ, TANGO AND RACE

BEFORE PERÓN.” Past & Present, no. 216, 2012, pp. 215–245.

-Robert J. Cottrol, Beyond Invisibility: Afro-Argentines in Their Nation’s Culture and Memory, 42 Latin Amer. Res. Rev., (2007)