By: Greg Ruppert

Roberto Clemente was a talented man on the baseball diamond but a better man off of it. Clemente’s baseball career flourished in the predominantly white league that is Major League Baseball. Clemente played 17 years as a Pittsburgh Pirate and was around during the worst parts of state-sanctioned segregation in U.S. history. For example, America was in the middle of Jim Crow segregation, which divided people into “colored” and white. In the 1940s to 1960s, Major League Baseball (MLB) had a inconsistent stance on Latinos players. As Adrian Burgos has shown, MLB leaders tied to Jim Crow were befuddled over the racial ambiguity of Latino players. He writes, “Those disturbed by the blurred line of exclusion called for renewed policing of the in-between space along the color line. This focus on Latinos showed that the segregationists’ most salient concern was not that blacks were passing as white but rather that they were entering organized baseball as Spaniards, Mexicans, or Cubans. The line between white and black was much clearer for team and league officials to police than that between a “Negro” and a “bronze-skinned” Cuban” (Burgos 2007, 162). The color-line began to break down in the mid-1950s, but Clemente suffered discrimination. Despite differential treatment, he shined on the diamond and was the pioneer that led the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates, who had an all-minority starting lineup, to the World Series Championship. How Roberto Clemente became a baseball legend in the United States? How he negotiated racism and adversity inside and outside the baseball field? And how did he became an inspiration in Puerto Rican, Latin America, and the U.S?

Racial Ambiguity in MLB’s history

The concept of racial ambiguity points towards many Latino players being categorized into different racial identities that they would not identify with if asked. In addition, racial ambiguity led to Major League Baseball’s bias because the MLB could recruit lighter-skinned Latinos as white players when baseball was beginning to desegregate. Still, it was harder to sign black players like Roberto Clemente. MLB officials looked down on the black Latino players, but so did their fellow teammates and sportswriters. For example, one of the years when Clemente led his Pittsburgh Pirates team to the World Series, the Pittsburgh area MLB writers slighted him in the voting as the best player. David Maraniss, the author of Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero, writes about the disrespect Clemente suffered when less talented teammates won awards while he was slighted. He writes, “When Groat had missed the last three weeks of the season with a wrist injury, Ducky Schofield had filled in well enough that the Pirates just kept winning. The second-place vote-getter also was a Pirate, again not Clemente. It was third baseman Don Hoak, the club’s tobacco-spitting vocal spark plug, whose statistics (.282 average, sixteen homers, seventy-nine runs batted in) were good but unexceptional … and yet another Pirate, Vernon Law, ace of the pitching staff, who would win the Cy Young award as the best pitcher. Finally, down in eighth place, there was Clemente, with 62 points from the writers, 214 fewer than Groat” (Maraniss 2007, 315). This shows the racism that still prevailed in baseball and how Clemente had to earn the respect of these writers to get the honors he deserved. Sportswriters would play favorites with the American-born white baseball players. In other words, MLB’s history was biased not only through rules of who could play but also through the voting that went on for many of the Major League Baseball’s awards like Most Valuable Player. How many more of these awards were given to white or non-black players because of the bias of sportswriters? How would the material lives of black Latino players like Clemente have changed with these recognitions?

While MLB Struggled Including Black Latinos, the Latin American and Negro Leagues Adored Them

What was going on during the years that Clemente joined and played in the MLB? How did the prevalence of Jim Crow Laws shape the Negro and other Latin American Leagues? First, the Jim Crow Laws were around in the 20th Century in the United States and these laws really limited integration between whites and non-whites. For example, Jim Crow Laws called for segregation where people of different skin colors must use different bathrooms, schools, churches, and many other facilities that are integrated today. In the MLB, Latinos were right in the middle of this segregation because many of these white elitists that played and owned the MLB teams were confused with the status of the Latino’s skin color. Beyond Jim Crow Laws, there was another presence that also impacted Major League baseball and Clemente’s development, which was the development of the Latin American baseball league and the Negro Leagues. First, the Latin American leagues were very integral because they helped combat the Jim Crow laws that outlawed non-white baseball players. For example, these leagues would open their arms to any people who were outlawed from playing professional baseball in North America. For example, one African-American ballplayer Willie Wells talks about the freedom he found in the Latin American leagues when he says, “When I travel with Vera Cruz we live in the best hotels, we eat in the best restaurants and can go anyplace we care to.” Comparing life in the Jim Crow North with that in Mexico, Wells concluded: “I’ve found freedom and democracy here, something I never found in the United States. I was branded a Negro in the States and had to act accordingly. Everything I did, including baseball, was regulated by my color. They wouldn’t give me a chance in the big leagues because I was a Negro, yet they accepted every other nationality under the sun” (Burgos 2007, 164). I think this is a very important point because Burgos talks about how the Latin American leagues had all different races play in their leagues and there was no prejudice or outrage. In my opinion, this is an important historical context because it shows you how slowly the MLB progressed in their concept of “equality”. Also, how Clemente had to literally fight through so much prejudice and hate to succeed in the Major League of Baseball during his playing career.

The Double Standard: Black and Latino in the MLB

Clemente always talked about the double standard in baseball. He was jeered because he was “black” and Spanish-speaking. These experiences all provide context on what was going on from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s. Clemente exercised restraint to be recognized as some of his white companions on the baseball diamond, even though he was a better baseball player than most of his colleagues. Think about it, one of the best players of all time had to fight to be treated equaly and be recognized. Rob Ruck, the author of Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game, summarizes Clemente’s predicament as follows, “When he was given a chance to play, Clemente was peremptorily taken out of the game if he did too well. “If I strike out, I stay in the lineup. If I play well, I’m benched,” he said. “I didn’t know what was going on, and I was confused and almost mad enough to go home.” (Ruck 2012, 432). Clemente was substituted out of the ballgame in the MLB if he did too well and did not mess up enough. Were other Black Latino ballplayer’s statistics hampered because of negligent treatment?

MLB’s Double Standard → MLB’s Gold Standard

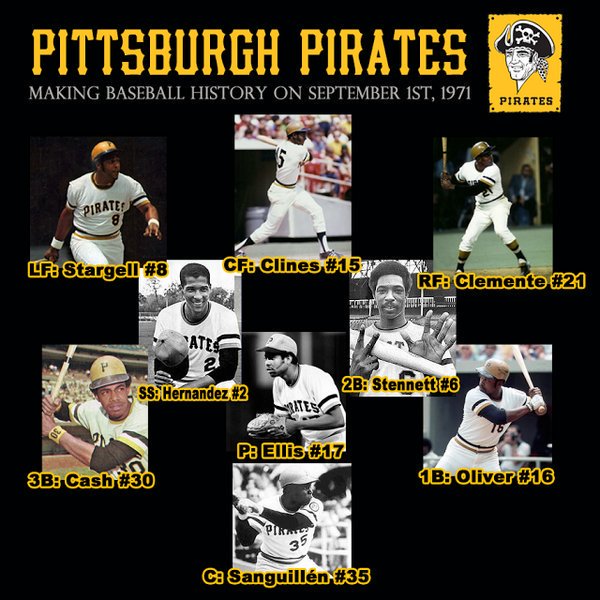

1971. Roberto Clemente leads an all-minority starting lineup to the World Series title. This title was a feat that sent ripples around the sports and entire world because it was the first time an all-minority lineup had won a major championship. This personal (and collective) achievement showed what the trailblazer Roberto Clemente was, moving the integrated baseball forward. Off the baseball diamond, Clemente was a giant. In Puerto Rico and Latin America, Clemente would hold baseball lessons to teach the children how to play baseball while also teaching them the about game of life. Also, Clemente died in a plane accident while providing aid to Nicaraguan victims of an earthquake. Clemente signed an endorsement deal with Eastern Airlines to get those necessary supplies to the victims faster and easier.

Lasting Legacy

Clemente impacted the Latin American players that would come to the MLB after him. Clemente made the transition easier for the Latino black ballplayers after him by experiencing the constant racism, hatred, and backlash. Clemente made it an honor for the succeeding MLB Latino players to wear the number 21. As Roberto Delgado states:

As a Puerto Rican, you understand how big Clemente was. Obviously, we can go into his stats, the Gold Gloves, the All-Star games, and the batting champions … but the legacy, that fight for justice, social justice, I think is more important.

Carlos Delgado, a former 1990’s Latino MLB player, on why he wears 21.

Works Consulted:

Burgos, Adrian. “Carlos Delgado Embraced the Legacy of 21.” La Vida Baseball, La Vida Baseball, 8 June 2019, www.lavidabaseball.com/carlos-delgado-clemente-legacy/.

Ruck, Rob. Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game. Beacon, 2012.

Maraniss, David. Clemente: the Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2007.

Burgos, Adrian. Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line. University of California Press, 2007.

Images Used:

First All-Black Baseball Lineup Plays in MLB, African American Registry, 31 Mar. 2021, aaregistry.org/story/first-all-black-baseball-lineup-plays-in-mlb/.

Maraniss, David. “No Gentle Saint.” The Undefeated, The Undefeated, 15 July 2016, theundefeated.com/features/roberto-clemente-was-a-fierce-critic-of-both-baseball-and-american-society/.